Floods and Landslides in Assam: A Warning or an Opportunity To Reorient Development?

by -

This is an updated version of the article that was first published on Gaon Connection on June 3, 2022.

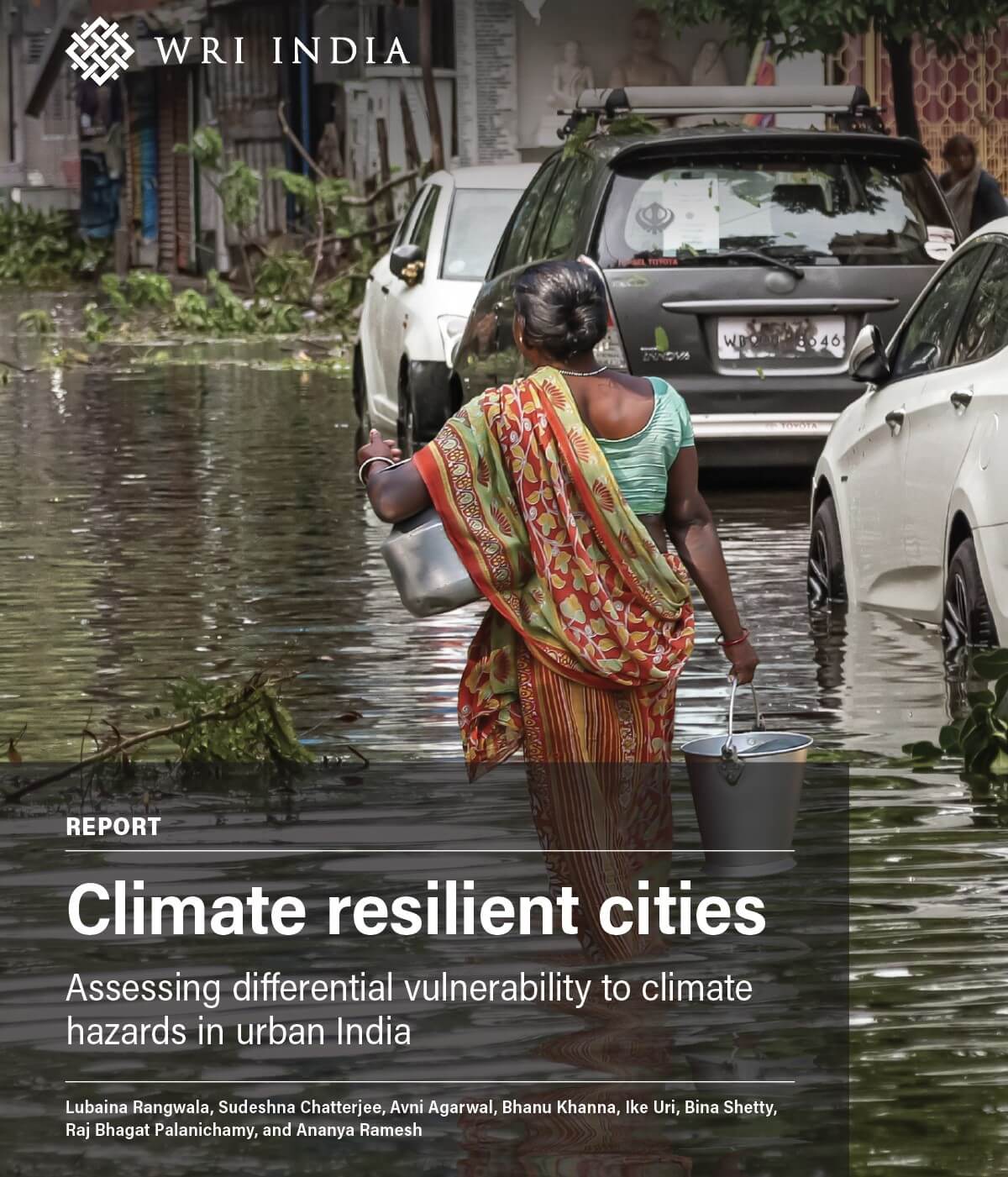

Earlier while traveling to my native village in the interior of Assam to meet my grandparents, I used to wait for the Barak Valley Express train at the New Haflong railway station. I always admired the lush greenery and scenic beauty in and around the station. A few weeks ago, in May 2022, I was shocked to see images of the entire railway station engulfed in waist-deep mud and debris, devastated by floods and landslides due to unusually heavy pre-monsoon rains.

The mayhem was not limited to this station alone and was not getting done just yet. Extensive damage to roads and railway lines along the Lumbding-Haflong-Badarpur section disrupted the supply of grains and vegetables to districts like Cachar roughly 300 km from Guwahati, causing the prices of these essential items to rise steeply. The same heavy pre-monsoon showers also caused waterlogging in parts of Guwahati city. The subsequent flash floods were even more severe. Major towns in Cachar, Karimganj (300 km from Guwahati), and Hailakandi (300 km from Guwahati) districts were inundated for more than 10 days without supply of electricity and clean drinking water in the most parts.

As the floods and landslides continued, 159 people lost their lives and more than 1,400 houses were damaged. At the peak of the crisis, more than 29 lakh people were affected across 25 districts. More than 76,000 hectares of cropland was under water.

Why did this happen?

Assam is prone to floods during the monsoon. However, the pre-monsoon rain was unusually intense this year. One factor could be the frequent and extreme weather events because of global warming, which is causing marine heatwaves and intensifying the water cycle. The recent “Code Red” report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change cautioned that the variability of monsoon precipitation in South Asia is likely to increase during the 21st century.

Secondly, deforestation and inadequate urban land-use planning along with the demand for land for agriculture and housing have led to the destabilization of hill slopes. Guwahati, for instance, has witnessed increased landslides due to increase in urbanization and house construction in hilly areas. Moreover, construction of major road, rail, and hydropower projects could also have exposed the region to impacts of heavy rainfall and flooding. Examples of recent infrastructure development include the East-West Road corridor that connects Silchar to Saurashtra, the conversion of the Lumding-Badarpur rail line to broad gauge, and upstream dams in Assam and Arunachal Pradesh. Though infrastructure development is needed in the region, if it does not take into account the increased risks due to climate change, ecological sensitivity and carrying capacity of the landscape, then such development could become maladaptive and increase the vulnerability to extreme weather events.

Opportunities for climate-resilient growth

The state of Assam is vulnerable to impacts of climate change and the yearly occurrence of these extreme events will not only lead to loss of lives and infrastructure, but also put a lot of financial stress on the state economy. It is imperative, therefore, for the state to climate-proof its people and infrastructure against future risks by integrating climate action and disaster risk management into the development agenda.

First, develop climate resilient urban development strategies with the active participation of local communities, experts, NGOs, research organizations, and other relevant stakeholders. For example, another flood-prone state, Kerala, is planning to develop a monitoring and evaluation framework to mainstream climate change strategies into state level planning and development process.

Second, develop and enact a framework to mainstream climate change adaptation objectives into sectoral policies and plans. This will require coordination among multiple stakeholders, institutions, and processes, but will ensure an efficient use of resources and investments and improve climate resilience and development outcomes for the state.

Third, align domestic budgetary resources with climate friendly development. For instance, Odisha undertook a rigorous cross-sectoral analysis to come up with the state climate budget for 2020-21. Such an exercise will assist the state in identifying policies and programmes that need to be strengthened or safeguarded from the perspective of climate resilience and mitigation.

Finally, tap into international finance by developing programmes and projects that transparently target climate mitigation and resilience outcomes within set timelines. For example, after the 2018 floods and landslides, the Rebuild Kerala Development Programme received finance of US$250 million from multilateral development bank to enhance resilience to climate change impacts.

By taking steps to reorient Assam’s development to mainstream climate concerns, the state can heed the warning from the floods of 2022 and emerge stronger and more resilient to future climate risks.

All photographs by Subrata Chakrabarty/WRI India.

Views are personal.